Zoanthid corals, affectionately called zoas by aquarium hobbyists in online forums (I guess because “zoanthid corals” is too long to type), are a trendy type of coral kept in reef tanks.

Why?

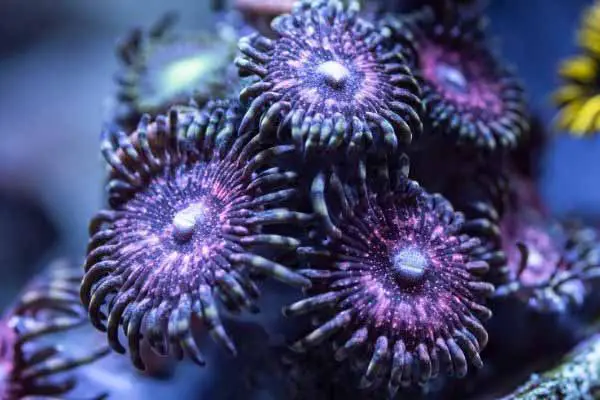

Because they are relatively easy to grow, maintain, frag, AND they are available in amazing, brilliant, fluorescent colors.

They are hardy and will grow well in most reef tanks, making them a great aquarium coral for beginners.

Table of Contents

You probably want to dive straight into everything you could possibly learn about zoanthids. And that’s fine. I’ve provided a handy list of links for easy navigation below. If you want the full benefit of my personal expertise, though, I strongly recommend you stick with me throughout the entire article. It’ll provide the best information for these awesome aquarium corals.

- Zoanthid Taxonomy and Identification

- Water Conditions for Zoanthid Corals

- Zoanthid Coral Placement

- Feeding Zoas

- Troubleshooting Problems with Zoanthid Corals

- Buying Zoas

- For More Information

Zoanthid Taxonomy and Identification

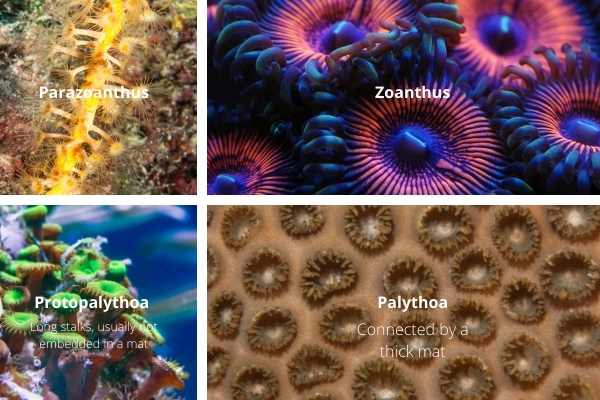

The term “zoanthid corals” tends to get used casually in the saltwater aquarium hobby for any large group of colonial coral button polyp animal. As is the case with other closely related organisms (and the baffling diversity we see on our reef systems), there remains some debate about the individual categorization of specific members within this group. I will attempt to characterize the classification in these two ways:

- Their growth form, or the way the colony grows

- The genus in which they belong (at least for now or at some point in scientific history)

Growth Forms

One of the primary ways to determine what genus and species a zoanthid colony belong to is to determine the growth form of the colony. There are three common colonial growth forms:

- Massive or Mat

- Connected

- Individual or Solo

You can hopefully see this illustrated in the image below:

Massive or Mat Colony Formations

These zoas generally belong to the Palythoa genus and are identified by a very thick mat, called a coenchyme or mesoglea. You can tell by looking at them that the mat is thick and substantial, making up a large amount of the weight of the entire colony. Some species will incorporate bits of rock, sand, or other matter to help make the mat even more substantial and structurally supportive/tough (Borneman 2001).

Connected

The next way some button polyp genera grow is connected at the base by a thin mat or runner. This thin connective tissue is called a stolon.

Individual or Sp;p

The last growth form is exhibited by certain genera that grow with individual stalks, not generally connected at the base.

Four Popular Genera

Now that we know how the various zoanthid polyps grow, concerning the relative connectedness within their colonies, it’s helpful to note that there are 4 genera of zoanthid corals you tend to find in the aquarium hobby:

- Palythoa

- Protopalythoa

- Zoanthus

- Parazoanthus

Water Conditions for Zoanthid Corals

Zoanthids require standard water parameters that are good for keeping just about any corals healthy. You’re aiming for tropical water temperatures (about 78F/25.5C), normal ocean salinity (somewhere around 1.025 specific gravity), normal hardness (8-12 dKH), and a pH around 8.0-8.4.

The key to keeping water parameters in the right range is to start with a high-quality salt mix.

Zoanthid Coral Placement

Place zoanthid corals in an area of low-medium to medium-high flow. Too much flow may make it hard for the polyps to open. You will know your zoanthids are “happy” if they open and are fully extended without seeming to stretch too far upright.

This is a generalization, and generalizations can be problematic in specific instances. Look to the vibrancy of the color of the coral as an indication of how much light the coral needs (and, therefore, a reflection on where to place the coral in terms of proximity to the brightest lights). The more intense and fluorescent the color is, the odds are the coral’s been exposed to high-intensity lighting u to that point. The more dull, drab, or darkly colored, the more shaded the zoanthid coral’s existence has been.

In terms of zoanthid placement, the best-case scenario is to know how and where the coral was placed most recently (if it came from a fellow hobbyist tank, for example). If it’s happily growing, try to recreate that in your tank. That is, of course, unless you know your placement will be better.

A group of different colored zoanthids together in the same area is sometimes called a zoanthid garden. You can learn more about those here.

How much lighting do zoanthids need?

Most zoanthids are rather forgiving/tolerant of different lighting; you can place them almost anywhere, excluding the darkest and brightest extreme areas of the tank. For starters, target a PAR around 80-120.

Many of the most popular “name-brand” zoas, like fruit loops, orange bam bam, fire and ice, and whammin’ watermelon, have eye-popping colors that will show the best when placed under actinic lights.

You could place them higher in the water column, too, assuming you properly acclimate them to the light intensity. That’s provided you don’t have more light-hungry corals in your tank.

Can zoas get too much light?

Be careful when first adding zoas to your tank that you don’t give them too much light, too quickly. Too much light could shock zoas and damage them. It is generally best to acclimate corals to intense aquarium lighting over several days.

Feeding Zoas

The majority of zoanthids have symbiotic photosynthetic zooxanthellae (I dare you to try and say that three times quickly). Therefore they’re best kept with at least moderate aquarium lighting. Some of the more brightly colored morphs will tolerate even intense lighting from metal halide, or newer generation LED lights if acclimated properly.

Most species are also capable of actively capturing prey. For the fastest growth of these corals, it’s recommended that you feed them periodically with an appropriately sized food, although feeding is not usually required.

Target feeding zoanthid coral polyps is fairly straightforward:

- If you’re using a small particle food like Reef Roids, you want to mix a small scoop of the dry food with a small bit of tank water, so the food/water mixture is thick and almost pasty.

- Turn off all of your aquarium pumps.

- Then, using your Sea Squirt, Julian’s Thing, pipette, or turkey baster, suck up the pasty food and very gently place a small number of food particles on each polyp, as close to the center as you can.

- For the most part, less is more. You don’t want to overfeed. As you get the hang of it, you can gradually increase the amount of food once you’re sure your corals are eating. But when you first start out, it is best to feed them very lightly.

- On many zoanthids, you can actually see the mouth slit. That’s the bullseye (or, more likely, the zoanthid mouth) you’re aiming for.

Since the food mixture is generally thick and heavier than water, it should gently fall on the polyp. The polyps will then very slowly fold inward, the mouth will open, and the food will go inside. This is the fastest and best way to grow these corals. Don’t forget that corals are animals, and animals like to eat. Yes, they can get some of their energy from the symbiotic zooxanthellae that live inside their tissue, but that is only half of the story. You will be rewarded with strong growth if you feed them regularly.

If your polyps won’t eat, try changing the size and type of food you are offering. Borneman reported that some individuals would only respond to certain food prey items.

Troubleshooting Problems With Zoanthid Corals

Polyps Not Opening

Some of the more rare and delicate zoanthid corals may take a couple of days to open after transportation to your home. If you just bought your polyps, don’t worry if they don’t open right away.

However, if your polyps were previously open and have recently closed, this should be taken as a serious sign of a water parameter issue. The first things I would check are salinity and pH. In my experience, zoas will close up if there are swings in salinity. I originally read about this in the book: Practical Coral Farming.

Algae growing over the corals

Carving out a niche to live in on a coral reef is tough business. There are lots of ways the inhabitants try to compete with each other, including chemical warfare, causing physical harm and even growing over one another.

Macroalgae do both, so you may have some problems with zoas growth if one of their neighbors are trying to grow over them. In that instance, adding algae-eating crabs, snails and sea hares may help.

Zoa Melting or Dying Back

Have you noticed that your zoanthid coral is dying back? There are a few common things to look for to help troubleshoot why your zoas are dying.

Zoa Pox

One disease that seems to disproportionately impact these corals is something called zoa pox or zoanthid pox. Zoa pox is the name given to the zoanthid disease characterized by tiny growths on the side of affected zoas. I’m not sure whether the growths/pustules themselves irritate the polyps and cause them to close up or if the coral is otherwise sickly and closed up (therefore showing the zoa pox). But the bottom line is that if you see zoa pox, you have a sick coral.

How do you treat zoa pox? One thread suggests hobbyists have been successful using Furan-2, suggesting zoa pox may be bacterial in nature (Furan-2 is an antibiotic).

“Someone Has Been Eating My Porridge Zoas!”

Another common problem with keeping zoas is predation. If you notice that your otherwise healthy zoanthids start disappearing, there are a few culprits to look for.

Watch carefully to see if one of your fish has acquired a taste for these polyps. Oftentimes, otherwise reef-safe fish like some butterflyfish, rabbitfish, or angelfishes can acquire a taste for coral polyps. Other times, the root cause of the disappearing act is from small invertebrates, like zoanthid eating nudibranchs. Just be careful not to throw the nudibranch out with the bathwater. Not all nudibranchs are bad. Some, like the Berhgia nudibranch, only eat Aiptasia anemones.

Buying Zoas

You will find zoanthid corals for sale at any respectable local or online fish store. Prices vary from just a few dollars ($5-10) for a small frag all the way up to the max you will want to pay for a high-end designer coral with a fancy name like orange bam bam or a purple hornet. These can sell for $100 or more for each individual coral polyp.

Top Zoanthids to Buy

One of the most fun aspects of keeping zoas in the saltwater aquarium hobby is to collect polyps from the hottest color morphs. They have ridiculous-sounding names that make perfect sense once you see them.

If you’re just getting started, here is a list of some of the names you can start with to find the perfect zoanthid corals for your reef tank.

- Fruit loops

- Purple people eater

- Orange bam bam

- Purple hornet

- Blueberry field

- Fire and ice

- Whammin’ watermelon

- Sunny D

- Rasta

- Red hornet

- My Clementine

- Blue hornet

- Radioactive dragon eye

- Utter chaos

- Blue agaves

- Night Fury

- Captain America

- Candy apple red

To see what some of these zoanthids look like, take a look at this YouTube video with a ranking of the top 10 most popular zoas:

Rare Zoanthids

Over the last few years, there has been a bit of zoanthid collector mania, driving up the prices of rare zoa color morphs. These rare zoanthid corals go by names like bubble buster, tazer, Tyree space monster, and bloodshot.

These corals are for the ultimate collectors with a lot of money, dreams of coral propagation, and an “I gotta have it” gene. These corals are so expensive and popular, there are forum threads that discuss the street value of these corals. (You can’t make that stuff up)

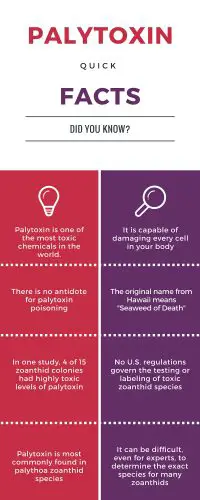

Danger: Palytoxin

Several species of zoanthids produce a toxic chemical called palytoxin, so individual specimens should be handled with extreme care. Palytoxin can cause neurological damage if it gets inside a cut, your eyes, or your nose or mouth. Always wear protective gear when handling zoanthids, including gloves and goggles.

Not every variety of zoanthid coral creates palytoxin. But make sure you let friends and family members know about it, just in case you ever run into an issue. A great way to do that is to document the issue in the back of your reef journal and let your family know where you keep it.

For More Information

If you are interested in hardy, fast-growing, brightly colored corals (and who isn’t?), then there’s probably a perfect zoanthid for you. Be sure to wear protective gear and always wash your hands when handling them, and most of all, take pictures and enjoy.

If you are looking for other amazing corals to add to your tank, check out:

References:

- Borneman, Eric H. Aquarium Corals. Microcosm Ltd; 1st Printing Edition (March 1, 2001)

Leave a Reply